How the data ecosystem is becoming medieval

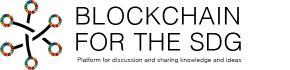

Unfortunately, our modern digital ecosystem is rapidly organizing as a feudal power structure erected in parallel with our existing power structures and freedoms. In the common conception of feudalism, a relatively small rentier class (lords) uses a variety of subtle and overt political and economic systems to extract value from the daily lives of the producer class (peasants), who generally have little choice or influence over the system. Users participate in platforms, often with only the barest knowledge of the data they surrender, and that data is then used to generate value exclusively for the platform owners. But there are far more parallels between our current digital ecosystem and feudal societies than can be described with broad strokes, and the commonalities are so striking that it could be argued that the digital ecosystem, and especially the social media ecosystem, constitutes a de facto feudal society.

Medieval Times

Before we get started, it’s important to briefly discuss the nature of actual historical feudalism. It wasn’t all, “Knights and Lords and Ladies, huzzah!” as we might think from popular media. That’s broadly referred to as chivalry. More accurately, there were definitely knights and lords and ladies (or whatever terminology a given society used for warrior and noble classes), but they were a very small part of the population, which was mostly serfs (or whatever term the landowners used to describe “the rabble”). To clarify the definitions, chivalry mostly encompasses all the “fun” parts of feudalism we like to see in movies and books. The other half of feudalism (the forced labor and masses of unwashed peasants beholden to a Noble lord) is mostly referred to as manorialism.

As might be expected of medieval political systems, most feudal societies are primarily centered around agriculture. The feudal system used to manage agricultural production and rural life in general is referred to as manorialism. In manorialism, a lord controls a certain area of land, which has usually been awarded to him by a more powerful lord or king. Peasants reside on this land, and they are generally politically and economically subject to the lord and his collection of various family members and retainers. More generally, peasants could be subclassified into freemen, who generally either owned their own parcel of land or paid some sort of monetary rent; serfs, who were obligated to work plots of land for their lord as a sort of unfree labor; and slaves, who were considered property and had few legal rights. Although there is still debate about the transition from slavery to serfdom as the dominant form of unfree labor in Europe, it is generally agreed that as slavery became less common in Europe, serfdom replaced it.

In many cases, serfs did have basic rights to things like common grazing land for livestock and small gardens for personal use, so they weren’t technically slaves. However, the serfs were also required to cultivate tracts of the lord’s land as a sort of forced labor or, under more capitalist feudal systems, pay (often exorbitant) taxes. In order to live and produce enough food to sustain themselves, the serfs had to bow to the production requirements of the lord. Similarly, because serf obligations were directly tied to the land that they occupied, any exchange of lands meant that serf obligations also transferred. In many cases, serfs were regarded as simply a productive feature of the land itself, much like a fruit-bearing tree or herd of deer.

A layout of a common manor. Mustard-colored areas are owned by the lord (the demesne) and crosshatched areas are owned by the church (the glebe). William R. Shepherd, Historical Atlas, New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1923. From Wikipedia.

Peasants, whether serfs or otherwise, were also often required to use the fee-based services provided by the lord’s manor. For example, many manors had grain mills that could be used by the peasants to grind their grain products into flour, but these mills also usually required fees or surrender of some part of the flour produced. In a way, these mills represent a sort of local monopoly, in which the only options available to the peasantry were to use the lord’s mill and pay its fees or to use no mill at all. The latter “option”, although notionally possible in some circumstances, would be functionally impossible because flour was one of the few easily stored calorie sources.

Judicially, the lord of the manor was generally in charge of all of his subjects. There were some exceptions (as one might expect from such a diverse and longstanding system as manorialism), and the judicial models of medieval feudalism varied somewhat, but generally, the lord created and maintained a court or series of courts that ruled over petty crimes and civil disputes. These feudal courts also existed to enforce whatever terms and conditions were imposed on the peasants and other tenants of the lord’s lands. Often, there were different rules and regulations governing each different type of occupant on a lord’s lands, and the courts generally managed these various obligations as well as any disputes that arose. Of course, there were also higher courts responsible for more severe crimes, and they were generally controlled by higher echelons of the nobility.

As with most systems of forced labor, swearing obligation and becoming a serf was much easier than escaping the peasantry. Generally, most serfs were locked into their social class. There were some ways to escape serfdom, but they varied based on society and even individual lord. Conversely, people with the misfortune of poverty or catastrophe often had to subject themselves to feudal obligation to survive. This typically involved some sort of ceremony binding the individual to the lord and his manor and potentially some sort of fee to take up residence. As might be expected, serfs usually lacked the mechanisms or resources to fulfill their obligations to the lord of the manor, so their families were perpetually bound to the land and the manor as unfree laborers.

Most manors were also inhabited by some number of freemen who weren’t obligated work the land via forced labor but did pay taxes, rents, and other dues. These freemen could be considered early versions of what might be called the “lower middle class” today, but the various classes of medieval society are so fluid and convoluted that any direct comparison is difficult. One easy way to think of freemen is as people who were rich enough to rent or buy land but not rich enough to have serfs work it for them. Thus, they had more freedom in terms of the business they engaged in, but they still had to do their own work. This is a gross oversimplification, and entire books have been written about the nature of freedom and freemen in each feudal society, but it gives a decent idea of the types of people who were considered freemen.

Some readers may already have some ideas of where this discussion is going, but it is important to explicitly parallel and contrast the current digital ecosystem with that of manorialism. This discussion will primarily center around social media companies, which are some of the largest and most mature data technology companies in the modern economy. Moreover, more traditional technology companies often seek to emulate social media companies in many of their data practices, so those will be examined as well.

The Serfs — Users

The power structures of modern social media and the surrounding data science ecosystem are highly reminiscent of feudal social and economic structure. Except instead of producing crops and livestock, the serfs of this system produce and surrender data in the course of their day-to-day lives, and the lords of this system are tech company executives, whose entire infrastructure is built upon the collection and exploitation of user data.

Before we go any further, it is necessary to address the “voluntary participation” or consent argument of social media. Anyone discussing the equity of the data science and social media ecosystem almost inevitably encounters the argument that participation in social media is voluntary. Although it may seem like a good standard, consent is broken and generally ineffective as a paradigm for modern digital data. Modern approaches to consent (e.g., “We track you, click here to surrender your data to us and we will do whatever we want with it until the end of time.”) can be seen as similar to the way medieval peasants “willingly” obliged themselves to become serfs. Although the situation is less physically brutal in modern society than in medieval society, when nearly all of a society’s personal and professional communication is digital, nonparticipation is voluntary ostracism. Nonparticipation is also nearly impossible in contemporary society, as brick-and-mortar stores give way to online orders, as any interaction between international phones demands exorbitant prices or free digital alternatives, as parties are planned and invitations are sent out via email and Facebook events, and as online job applications become the only job applications.

This formulation doesn’t even broach the fact that for many disabled and differently abled individuals, the digital option is the only option, bringing it even closer to the “submission or death” situation. The Internet has given unprecedented freedom to many people who were previously isolated or dependent on caregivers. But with the modern internet, the caveat is always that anything you order or say will be tracked by someone, regardless of how necessary it is for your life.

If we accept that nonparticipation is a false or, at least, extremely burdensome option, then participation in the system is the primary state of being. In terms of participation, one key difference between medieval manorialism and digital feudalism is that no person is obligated to just one platform. Instead, every person has a web of obligations to different digital manors, each of which demands different data in exchange for use. For those who are concerned with privacy, then, the question becomes how much data they are willing to surrender to how many lords and whether their personal and professional life can accommodate those decisions.

As cloud-based services like Office 365 aggressively invade businesses, this decision becomes moot. Traditionally, your time is not your own at work, and your employer has always known your general schedule, output capacity, and work style. But now another third-party company knows all of those things as well, and they can easily pair them with data collected from other companies. Your time and work output might belong to your employer, but now they also do work for a second company, which uses them to do things that don’t belong to your employer. The invasion of cloud-based services into business environments is the corporate mediatisation of digital space, as previously sovereign digital environments, such as local corporate servers, cede the obligations and rights of data storage and use to third parties. In many cases, your employer may be in the exact same situation as you are in terms of choosing to surrender their data. A useful conceptual framework for corporate “cloud service” clients is as knights or minor lords, granted space and access by the lords of a platform and in charge of their own fiefdom of serfs.

One of the key disparities between the societal groups that participate in digital feudalism is the insistence that individual data is functionally worthless but aggregate data is sufficient to drive the valuation of the largest companies on the planet. This disparity (or, if you are feeling charitable, “scaling effect”) is at the heart of digital feudalism, and it is something that traditional serfs did not have to address. It is easy for a serf to appreciate the value of the grain or other crops surrendered to the lord of the manor, and it would be difficult for any lord to reasonably argue that food is worthless, especially during times of famine. There is a reason many revolutions were sparked by droughts, price controls, and other events that restricted food availability. Starvation is a powerful motivator in a way that privacy is not.

Data collection companies exploit these blind spots and insist that a single person’s data has no meaningful value except in aggregate. One could also argue that a single dollar in Facebook’s $600+ billion valuation is functionally worthless compared to the aggregate, so why aren’t they expected to surrender that “worthless” money to the people who generate the bedrock of their value? Of course, that question is intentionally somewhat obtuse, but it illustrates the fundamental power imbalance between the lords of the digital manors and their users. They decide on the value of your data, but they also insist that whatever benefit they provide you is of equal worth (minus whatever profit they extract). In digital manorialism, platform owners are strongly disincentivized from ever estimating the worth of a single person’s data while they gleefully value their aggregate data in astronomical terms.

The Gentry — Corporate Partners and Power Users

These power imbalances are further exacerbated by the fact that, the legal systems of digital and medieval feudalism also have many similarities. The “low courts” of digital manors are whatever reporting systems and staff they choose to use, and the crimes they oversee on their platforms have grown up organically. Harassment is a serious and legitimate crime, but most of the investigative and punitive power over incidents of digital harassment has been ceded to platform owners. You can certainly file a report with the police, but if someone is harassing a person from another state or country, the victim has little recourse beyond those systems established by the lords of a given platform. Copyright complaints often follow a similar pattern with the added layer of extremely stringent legal structures demanding that platform owners implement policies so aggressive that Digital Millennium Copyright Act takedown requests can themselves become tools of harassment.

As might be expected, these systems are often wholly inadequate to defend the rights of the “serfs” and tend to favor the rights of “allied classes” in the digital feudal structure. Media companies pay top dollar to advertise, both overtly and covertly, on social media platforms, so if they complain that someone is using their intellectual property, then platforms will absolutely jump on it. But what if a company steals your art or music without consent? Well, you better have your own social media outlet and a big following because otherwise maybe they’ll get around to it a few weeks from now when their big client has already profited handsomely.

In between massive companies that use social media platforms and their data for their own strategies lies a curious collection of “minor gentry”, or “Influencers.” These are people who gain a variety of perks or income from social media. They are only rarely actual employees of media platforms, but they do get paid (usually via “partnership programs”) for drawing more users into the platform, and thus, enhancing the data flows of the platform lords. Of course, they are obligated to the platforms that host them, but there is no reciprocal obligation from the platform. Many platforms will gleefully host the most revulsive content if it gains them huge numbers of users, but they will abandon that content the moment anyone starts discussing boycotts or advertisers threaten to leave.

The most successful of the digital gentry even stand to gain their own subplatforms, networks of sites built around their core audience, or lucrative full-time jobs distributed as rewards from platform lords. These subplatforms generally serve to provide a sense of autonomy without any actual freedom from data collection and exploitation. Often this involves perks like the ability to create multiple accounts around a “brand” while most individual users are pushed to only use their true identity, if multiple accounts are even an option. Many platforms expressly prohibit multiple accounts unless, of course, you run a business on their platform. When you have a business (or claim to have a business), your access to data accrued from the platform also increases. But you are never given full access to all data, even the data your subplatforms bring in because the lords of your platform are, of course, “seriously concerned” about the data privacy of their users. Translated cynically, this means that subplatform owners simply aren’t powerful or wealthy enough to warrant full access.

Lords and Kings — Platform Owners

Finally we come to the much-discussed lords of our digital manorialism. These are the people who own and control massive platforms and all of the data they generate. It is often tempting to discuss ownership in terms of corporate entities or organizational structures, but that neglects the core understanding of this group: they are (mostly white, mostly male) people. They decide the privacy and sales policies of their platforms. They reap the mind-blowing income of user-generated data. They sign off on any new schemes to acquire more data or to be more aggressive in the assertion of their rights as sovereign rulers of their digital domains.

It is important to understand the nature of the power structures erected by digital manorialism, and it is wrong to assume that platform owners are universally malevolent or benevolent. Many attempt to be good people and may see themselves as good people. But they lead corporations, and the singular goal of a corporation is to generate revenue. Because user data is their core value offering, digital lords are forever driven to encroach on user privacy and enhance data collection efforts, lest their power be usurped by someone more willing to maximize data collection. Platform owners forever walk on the edge of balancing new ways to extract data against the risk of users abandoning their exploitative environments. This is much the same as manorial lords who were expected to supply tithes, taxes, and conscriptional levies to their patrons or Kings while still ensuring that their own manor prospered. But in digital manorialism, the ultimate power is not the ruler or rulers of a nation, but rather the economic forces of a financial market. Ironically, the organizations that extract value from their users are, in turn, beholden to collective groups of investors, although most of their users will never be wealthy enough to acquire sufficient ownership to defend their own rights.

To legitimize these power imbalances, manorial systems almost always revert to some mechanism of contractual fealty. Historically, serfs submitted or were generationally subject to a contract or agreement, the terms of which were set by their lord. In modernity, the contracts of digital manorialism are interminable User Agreements, many of which include so many clauses and such exploitative terms that they are unenforceable in many jurisdictions. User Agreements are rarely, if ever, presented in simple terms, and they are often so lengthy that they would require multiple days of reading and probably a legal degree to fully understand. Thus, User Agreements represent another piece of the artifice symbolizing user choice.

Data sharing settings are another tool in the lordly arsenal of data collection. Ostensibly, these settings allow users to manually control what data they share with others. However, this is only true in some circumstances, and the maintenance of these settings generally requires constant vigilance. In many cases, during updates or revamps, users are defaulted to the most permissive data sharing settings, and they must manually reset their preferences after every update. The most nefarious of these resets assumes backward assent: if your preferences default to sharing a particular piece of data, then the platform immediately has permission to share all of the historical archive of the data. In this way, “privacy controls” do not prevent storage; they simply restrict the sharing of this information.

Users don’t always even have these illusionary choices of assent. As data science grows, so too does a new field of employee quantification. Unfortunately, the Quantified Worker movement is simply Taylorism with a thin veneer of technology smeared over its face and adopted in a society without the labor protections of the past. But the service providers doing the quantification are almost always third-party data platforms looking for new partners to make their data collection strategies mandatory. It is no longer a single employer enacting these policies, but rather multiple powerful employers or even government entities collaborating to maximize the quantification of worker performance. Naturally, the serfs of these digital enterprises are always referred to as “users” or “participants” or some other term implying the ability to opt out, when they are actually more like subjects, whose options are to surrender their data to a third party or lose their job. Predictably, the workers subjected to these mandatory data extraction schemes can be separated into unionized workers who successful fight off these intrusions and non-unionized workers who see their quality of life and work diminish sharply as they desperately struggle to keep their jobs while performance benchmarks ratchet skyward.

So we are left to wonder what sort of event could spur more serious regulation of user/consumer privacy. You might make a logical argument for something like large security breaches or leaks, but that’s already a daily problem, and no company seems particularly worried about them. They just add the cost of an investigation into their risk management calculations and carry on as usual. What are you going to do, stop using banks because your identity was stolen in the Equifax breach? You may think that the security of your data is extremely important, but to a data company, the only difference between a successful sale and a security breach is how much they get paid for your data.

The Way Forward

It is clear that manorial systems are not compatible with egalitarian and free societies. But the trend toward digital manorialism is relatively young, and we have an opportunity to reverse course before it becomes too entrenched. The more established manorial systems become, the more broken they become, and if they continue unabated, users may find themselves as subjects of a digital Ancien Regime. There are many options to address the issues of digital manorialism without directly attacking the significant innovations and opportunities of data science. If users are generating value for a company, then they should consider unionizing. Most of the barriers to traditional unionization are linked to employment status, but platform owners have been extremely careful to ensure that users are not in any way considered employees. Although various groups have attempted to conduct social media boycotts or blackouts, they were often poorly organized or ad hoc efforts. Continuous stable user unions would offer significant leverage to break the most egregious exploitations of digital manorialism or even stymie them before they begin. They could also provide leverage for employees subjected to mandatory third-party data collection and could meaningfully lobby for regulation from the political system.

Any sustained equality between platform owners and users requires strong privacy laws and policies, which can only be effectively enacted and enforced by political institutions. In some cases (such as China), the platform owners and political policymakers are closely aligned, if not the same groups, which represents an extremely dangerous paradigm. But in many other cases, the lords of the data manors are distinct from the political apparatus, and the history of digital manorialism is one of political inaction. Many political systems, especially in the United States, have significant gaps in technological knowledge, as evidenced by Mark Zuckerberg’s testimony before Congress after the election interference scandal of 2016. This makes it more difficult for politicians to effectively defend the privacy and rights of their constituents, if they are even so inclined to do so. The European Union recently made great strides toward defending user privacy with the General Data Protection Regulation.

The bonus of these types of user-focused political efforts is that they have knock-on effects for users they do not directly protect. Many data companies are global, and it is not feasible for them to institute different protections in each region and remain compliant with GDPR and other regulations, so they frequently adopt blanket policies that comply with the most stringent regulations. This can already be seen in the new notifications and privacy options that appear in platforms operating in the EU, even if users and corporate offices are not located in that jurisdiction. As these laws and policies proliferate across the globe, companies may eventually become more selective in their blanket implementations of various rules, but for now, these are excellent tools not just to protect the citizens of one nation, but of all users of the digital commons.

Because that is what is at stake. The internet’s promise as a global intellectual commons has been partitioned into fiefdoms without input from the users inhabiting that commons. If we can change this trend now, before it becomes too entrenched, we can enhance not only the privacy but also the quality of life of everyone who interacts with digital technology.

Credits: Zach Scott