The Merriam-Webster defines privacy as freedom from unauthorised intrusion. Data privacy is not necessarily about secrecy or having something to hide. It is about control related to the use and disclosure of data (Cavoukian, 2017); the capability to choose whether the information is disclosed to others and determine how it is used, as mentioned by Steven T. Snyder (2019). Snyder also added that “The highest degree of privacy for an element of information would be if its owner had complete control over its dissemination and use for as long as the information exists” Also, that the enforcement of privacy is how security will be defined encompassing the mechanisms used to ensure the confidentiality, integrity and availability of information. The notion of control and freedom of choice is critical to privacy. According to Cavoukian (2017), respect for the privacy of all individuals in a society not only forms the bedrock of freedom but also of innovation and its resulting prosperity. However, data privacy is being eroded.

Large organizations see enormous potential and value in correlating vast amounts of data to decipher trends, interpret behaviour and formulate predictions. Data collected is intended for value-added services, such as to personalise and enhance the user experience, to offer suitable or new services, bring efficiencies and convenience to the end-user. This creates economic and social value, beneficial for business and considered as a highly valuable asset. Entities holding such data believe that this data is collected via various data collection techniques, investment, and obtaining consent. Therefore, it belongs to the data collector, and they should be the ones controlling it.

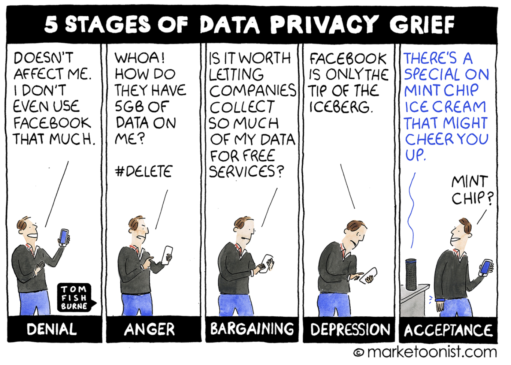

Consent is usually obtained through fine-print terms and conditions agreements. It is general knowledge that “no one reads that”. Mainly, because people have given up on making that effort, let alone being able to understand, against the convenience of ignoring and moving forward to get to what they want to do by using any particular service or application on the web. Most of us do not resent that our smartphones or wearable devices allow our location, activity or health status being tracked continuously for the ability to navigate our way or show our health or activity levels through a few clicks on an app. The biggest IT companies have gained enormous wealth by harvesting and commoditising the information by exploiting data about their users, who expect privacy.

With pendular inclinations towards their duties of citizen’s protection and privacy rights, governments collect data and perform uninvited or secretive surveillance for control, for protecting its citizens from harm, mostly justified in the name of security, detecting threats to the security or finding terrorists (“needles in haystacks”).

In both cases, what is stored where, how secure is it, whom it is shared with, how it is interpreted and what that leads to, is unknown? Not having answers to these questions contributes to the lack of transparency and erosion of our privacy, and as a result, loss of trust in third parties, that we depend on to run our modern lives.

According to United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD, n.d.), “107 countries (of which 66 were developing or transition economies) have put in place legislation to secure the protection of data and privacy. In this area, Asia and Africa show a similar level of adoption, with less than 40 per cent of countries having a law in place”. However, in the age of our fast evolution of the ubiquitous information technology, the law is, by and large, trailing behind the innovations. There is a growing gap between data privacy laws and the way information is collected, processed, stored, shared or ensured that it can be trusted to be consistent with the interests of the people; giving people control and freedom of choice.

DLT or Blockchain technology comes with a promise where:

- Users are not required to trust any third-party and are always aware of the data that is being collected about them and how it is used.

- The users are the owners of their personal data.

- Third parties can utilise the user’s data, as authorised, without being responsible for securing data. On a public Blockchain, details of every transaction can be made available, easily accessible by government agencies, business partners or even co-workers without the need for revealing their personal details, unless authorised.

In case of cryptocurrency such as the Bitcoin, there is no room for a centralised or third-party intervention. Other than the transaction fee, all other details are concealed with no intervention between transaction parties. Although a log of every transaction is kept, personal information is protected by anonymising the data by only storing a hash value of people’s identity for the transactions. Therefore, information on a Blockchain cannot be used to trace transactions back to a particular individual just by examining a Blockchain, as it is nearly impossible to associate transactions with a real person’s identity.

References:

- Cavoukian, A. (2017) ‘“Global privacy and security, by design: Turning the ‘privacy vs. security’ paradigm on its head”’, Health and Technology, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 329–333 [Online]. DOI: 10.1007/s12553-017-0207-1.

- Steven T. Snyder (2019) The Privacy Questions Raised by Blockchain [Online]. Available at https://www.bradley.com/insights/publications/2019/01/the-privacy-questions-raised-by-blockchain (Accessed 15 May 2019).

- UNCTAD (n.d.) Data Protection and Privacy Legislation Worldwide [Online]. Available at https://unctad.org/en/Pages/DTL/STI_and_ICTs/ICT4D-Legislation/eCom-Data-Protection-Laws.aspx (Accessed 19 May 2019).

Also read:

Top 10 Blockchain implementation Challenges

How will Blockchain Dominate Technology